Weather Modification in California: Part 1

Dan Titus, April 24, 2025

This series of articles provides an overview and history of weather modification programs in California denoting the genesis and costs of these programs. Listed are agencies involved with weather modification cloud seeding programs and laws requiring public notification for programs. Also listed are the top contractors currently licensed to do this activity in the State. Included is a schedule of costs for weather modification programs. Also discussed is success rate contrasted with detrimental effects and legal challenges of these programs. Environmental and safety is discussed in relation to current technologies and patents. Part 2 will discuss are large-scale geoengineering programs and their current status.

Atmosphere interventions have been a topic of scientific and regulatory interest for decades. However, interventions raise significant public safety concerns, including environmental impacts, unintended consequences, and equitable distribution of resources. In response, jurisdictions in California and across the United States have developed or are developing rules and regulations to govern weather modification activities.

Types of Interventions

While the terms “weather modification,” “cloud seeding,” and “geoengineering” are sometimes used interchangeably, they represent different scales and approaches to deliberately altering the Earth’s atmospheric processes. The key differences lie in scale (local vs. global), duration of effects (temporary vs. long-term), and purpose (addressing immediate weather conditions vs. combating climate change).

Weather Modification is the broadest term, covering any deliberate attempt to alter local weather conditions. This includes both cloud seeding and larger-scale intervention techniques. Weather modification typically targets specific local weather events like fog, precipitation, or hail.

Cloud Seeding is a specific weather modification technique that involves introducing substances such as silver iodide, potassium iodide, or dry ice into clouds to encourage precipitation. It works by providing additional condensation nuclei that water vapor can attach to, forming droplets heavy enough to fall as rain or snow. Cloud seeding is limited to local areas and specific cloud types, with effects lasting hours to days.

Geoengineering refers to the deliberate large-scale intervention in the Earth’s natural systems to counteract climate change

Geoengineering operates on a much larger scale, aiming to deliberately manipulate the Earth’s climate system to counteract climate change effects. Rather than affecting local weather, geoengineering targets macro global climate patterns. Techniques include:

- Solar radiation management (reflecting sunlight back to space)

- Carbon dioxide removal from the atmosphere

- Ocean fertilization to increase carbon uptake

Here’s a table summarizing the key differences:

| Feature | Cloud Seeding | Weather Modification | Geoengineering |

| Focus | Precipitation | Weather alteration | Climate change mitigation |

| Scale | Local | Local to Regional | Global |

| Timeframe | Hours to Days | Days to Weeks | Years to Decades |

| Risk | Low | Moderate | High |

| Specificity | High | Moderate | Low |

| Reversibility | Relatively High | Moderate | Potentially Low |

| Example | Silver iodide to increase snowfall | Hail suppression | Stratospheric aerosol injection |

Success Rates

Cloud seeding programs in California have reported varying degrees of success. Studies suggest that cloud seeding can increase precipitation by a marginal 5–15% under optimal conditions. However, the effectiveness depends on atmospheric conditions, seeding methods, and monitoring accuracy. Examples include Sierra Nevada Programs, estimated at 5–10% increase in snowpack and Central Valley Programs noting modest increases in rainfall, particularly during winter storms.

The History of Weather Modification and Cloud Seeding Programs in California

Cloud seeding program initiatives in California represent a long-standing effort to address the state’s water challenges through weather modification. These programs have demonstrated marginal success in augmenting precipitation. The involvement of federal, state, and academic entities, along with private contractors, highlights the complexity of these initiatives. As California continues to face claims of climate variability and water scarcity, cloud seeding will likely remain a tool in the state’s water management arsenal. However, the efficacy of cloud seeding remains a topic of ongoing research and is not without controversy. Ongoing scrutiny and debate over its efficacy and impacts continue.

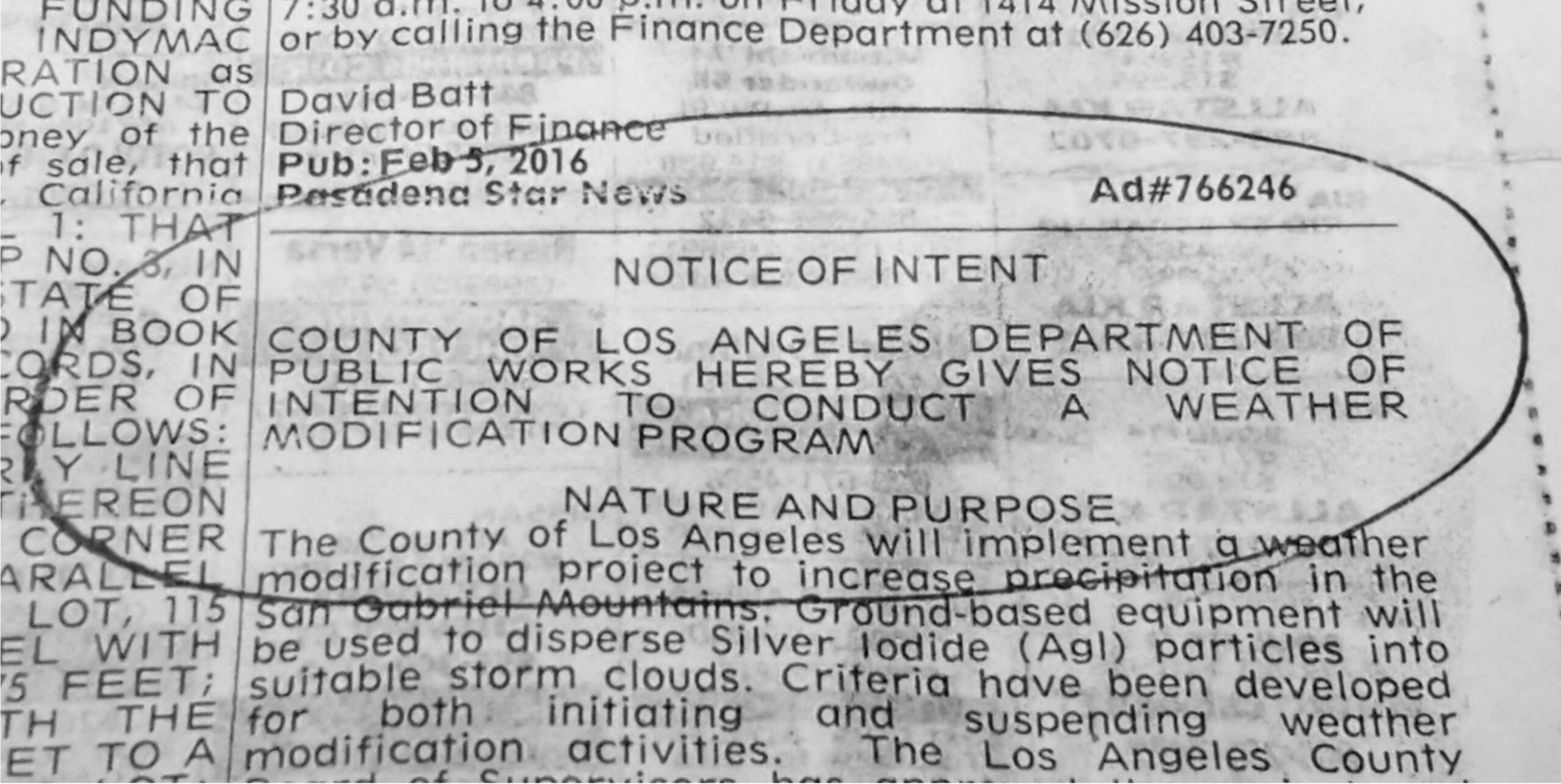

Cloud seeding, the process of dispersing substances into the air to encourage precipitation, has been employed in California since the mid-20th century. The practice involves dispersing substances like silver iodide or potassium iodide into clouds to encourage the formation of ice crystals, which can then grow and fall as precipitation.

Genesis of Cloud Seeding in California

The history of cloud seeding in California dates back to the 1940s and 1950s, when scientists began experimenting with weather modification techniques. The first significant cloud seeding experiments in California were conducted by the U.S. military and private companies in the 1940s. The discovery that silver iodide and other nucleating agents could enhance precipitation led to widespread interest in cloud seeding as a tool for water resource management.

In the 1950s and 1960s, California saw a surge in cloud seeding projects, particularly in the Sierra Nevada mountains, where water supply is critical for agriculture and urban areas. The state’s reliance on snowpack for water storage made cloud seeding an attractive option to augment water supplies during dry years.

- Early Efforts (1940s–1950s):

- The genesis of cloud seeding in California can be traced back to the 1940s and 1950s, when the U.S. military and federal agencies began experimenting with weather modification technologies. The U.S. Army Signal Corps and the Office of Naval Research conducted some of the earliest experiments.

- In 1946, General Electric scientists Vincent Schaefer and Bernard Vonnegut discovered that silver iodide could be used to induce ice crystal formation in clouds, laying the foundation for modern cloud seeding.

- Federal and State Involvement (1960s–1970s):

- The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (USBR) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) became key federal players in weather modification research during the 1960s and 1970s.

- California established its own cloud seeding programs, often in collaboration with federal agencies, to address water shortages. The California Department of Water Resources (DWR) became a central state agency overseeing these efforts.

- University Research:

- Universities, such as the University of California and the Desert Research Institute (DRI) in Nevada, have played a significant role in researching and evaluating the efficacy of cloud seeding. Their studies have focused on atmospheric science, cloud physics, and the environmental impacts of seeding.

- Military Involvement:

- The U.S. military supported weather modification research, including cloud seeding, for both civilian and strategic purposes. Projects like Project Stormfury (1960s–1980s) explored hurricane modification, but much.

- Modern Era (2000s–Present):

- Cloud seeding programs in California have continued to evolve, with a focus on improving technology and ensuring environmental safety. Programs are often funded by a combination of state, federal, and local water agencies.

Agencies Involved in Weather Modification Programs

In California, the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) oversees the permit process and licenses contractors for weather modification programs, including cloud seeding. The DWP The DWR regulates these activities under the state’s Water Code, ensuring that weather modification projects are conducted safely and in compliance with environmental and legal standards. The specific section of the California Water Code that deals with weather modification, including cloud seeding, is Division 6, Part 2, Chapter 2, Sections 23500-23515. These sections outline the regulatory framework for weather modification activities, including the permit process and licensing requirements for contractors. The DWR is responsible for overseeing these activities under this legal framework. Key provisions include:

- Section 23500: Definitions related to weather modification.

- Section 23501: Requirement for a permit to conduct weather modification.

- Section 23502: Application process for permits.

- Section 23503: Grounds for denial of a permit.

- Section 23504: Conditions for permit issuance.

- Section 23505: Reporting requirements for permit holders.

California’s cloud seeding programs involve a collaboration of military, federal, state, and academic entities.

Military research laid the groundwork for modern cloud seeding techniques

Below is a list of key agencies and organizations involved:

- Federal Agencies:

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA): Provides research, oversight and efficacy on weather modification.

- Bureau of Reclamation: Funds and supports cloud seeding projects in the western U.S., including California. U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (USBR): Provides funding and technical support for cloud seeding projects.

- National Science Foundation (NSF): Funds academic research on weather modification

- State Agencies:

- DWR: The primary state agency responsible for water management and cloud seeding programs.

- California Air Resources Board (CARB): Monitors environmental impacts of cloud seeding.

- California State Water Resources Control Board: Regulates water rights and permits for cloud seeding.

- Local Water Districts: Collaborate with DWR to implement seeding operations in specific regions.

- Military Involvement:

- Historically military research laid the groundwork for modern cloud seeding techniques. The U.S. Air Force was involved in early weather modification experiments.

- Universities and Research Institutions:

- University of California, Davis: Conducts research on cloud seeding efficacy and environmental impacts.

- Desert Research Institute (DRI): A key research partner in cloud seeding programs. Provides expertise in atmospheric science and monitoring.

- Permitting Agency:

-

- California State Water Resources Control Board: Issues permits for cloud seeding activities under the California Water Code.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA): Conducts research on atmospheric science and cloud seeding efficacy.

- National Science Foundation (NSF): Funds academic research on weather modification.

Top Contractors Licensed for Cloud Seeding in California

Several private companies are licensed to conduct cloud seeding operations in California. These contractors work in collaboration with state and federal agencies. Notable contractors include:

- Weather Modification, Inc. (WMI): A leading cloud seeding company with operations in California.

- North American Weather Consultants (NAWC): Specializes in weather modification programs in California and across the western U.S.

- Aero Systems Incorporated: Provides cloud seeding services and equipment.

Costs of Weather Modification Programs (2000–2024)

The costs of cloud seeding programs in California vary depending on the scale and location of operations. Below is an estimated schedule of annual costs:

- 2000–2010: $1–2 million annually, primarily funded by state and local water agencies.

- 2011–2015: $2–3 million annually, with increased funding during drought years.

- 2016–2020: $3–5 million annually, driven by severe drought conditions and expanded programs.

- 2021–2024: $5–10 million annually, reflecting heightened investment in water augmentation technologies.

These costs cover equipment, personnel, materials (e.g., silver iodide), and monitoring. Funding sources include state appropriations, federal grants, and contributions from local water districts.

Substances Used for Weather Modification Cloud Seeding

Cloud seeding is a weather modification technique used to enhance precipitation, disperse fog, or mitigate hail. The main substances used in cloud seeding include:

- Silver Iodide (AgI):

- Mechanism: Silver iodide has a crystalline structure similar to ice, making it effective as a nucleating agent. When dispersed into clouds, it provides a surface for water vapor to condense and freeze, forming ice crystals that can grow and fall as precipitation.

- Usage: Commonly used in both cold and warm cloud seeding.

- Sodium Chloride (NaCl – Common Salt):

- Mechanism: Salt particles are hygroscopic, meaning they attract and hold water molecules. When dispersed into clouds, they can enhance the coalescence of water droplets, leading to larger droplets that can fall as rain.

- Usage: Primarily used in warm cloud seeding.

- Dry Ice (Solid Carbon Dioxide – CO₂):

- Mechanism: Dry ice is extremely cold (-78.5°C). When introduced into a cloud, it causes the surrounding air to cool rapidly, leading to the formation of ice crystals that can grow and precipitate.

- Usage: Typically used in cold cloud seeding.

- Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂):

- Mechanism: Similar to sodium chloride, calcium chloride is hygroscopic and can attract water vapor, promoting droplet growth and coalescence.

- Usage: Used in warm cloud seeding.

- Potassium Iodide (KI):

- Mechanism: Potassium iodide can also act as a nucleating agent, though it is less commonly used compared to silver iodide.

- Usage: Used in some cold cloud seeding operations.

- Liquid Propane:

- Mechanism: When released into the atmosphere, liquid propane expands and cools rapidly, causing the surrounding air to cool and form ice crystals.

- Usage: Used in some cold cloud seeding techniques.

Methods of Dispersion:

- Aircraft: Substances are dispersed from aircraft flying through or above the clouds.

- Ground-Based Generators: Devices on the ground release seeding agents into the atmosphere, where they are carried upward by air currents.

- Rockets and Artillery: In some cases, rockets or artillery shells are used to deliver seeding agents directly into clouds.

Substance Use: Health Warnings

Below is a table summarizing the main substances used for weather modification cloud seeding, including their names, approximate dates of development, and potential health warnings based on Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS) information.

- Dates Developed: The dates are approximate and refer to when these substances began to be widely used in cloud seeding programs.

- Health Warnings: These are based on general MSDS information and may vary depending on the concentration, form, and exposure levels. Always consult specific MSDS for detailed safety information.

- Environmental Impact: Many of these substances are considered safe in small quantities, but their environmental impact, particularly on aquatic ecosystems, should be monitored.

| Substance | Date Developed | Potential Health Warnings |

| Silver Iodide | 1940s | – May cause respiratory irritation if inhaled. – Can cause eye and skin irritation. – Toxic to aquatic life. |

| Sodium Chloride | 1940s | – May cause irritation to eyes, skin, and respiratory tract. – Excessive inhalation can cause coughing or shortness of breath. |

| Dry Ice (CO₂) | 1940s | – Can cause frostbite on contact with skin. – Inhalation in confined spaces may lead to asphyxiation. – Non-toxic but hazardous in high concentrations. |

| Calcium Chloride | 1940s | – May cause skin and eye irritation. – Inhalation can irritate the respiratory tract. – Ingestion can cause gastrointestinal discomfort. |

| Potassium Iodide | 1940s | – May cause skin, eye, and respiratory irritation. – High doses can affect thyroid function. – Generally low toxicity. |

| Liquid Propane | 1970s | – Extremely flammable. – Inhalation can cause dizziness or asphyxiation. – Contact with skin can cause frostbite. |

| Urea | 1960s | – May cause mild skin and eye irritation. – Inhalation of dust can irritate the respiratory system. – Low toxicity overall. |

Legal Challenges

Cloud seeding programs have faced legal challenges over the years. Notable cases include:

- 1950s–1960s: Early lawsuits by farmers and landowners who claimed cloud seeding caused flooding or disrupted natural weather patterns.

- 2000s: Legal disputes over water rights and the allocation of augmented water supplies.

- 2010s: Environmental groups raised concerns about the ecological impacts of silver iodide, leading to stricter permitting and monitoring requirements.

Legal challenges highlight the tension between technological innovation and regulatory oversight. Courts have generally upheld the legality of cloud seeding, provided it is conducted in compliance with state and federal laws. However, the lack of clear regulatory frameworks has led to ongoing disputes, particularly in water-scarce regions like California.

Critics argue that cloud seeding can lead to inequitable distribution of rainfall, environmental harm, and potential liability for damages caused by altered weather patterns. Legal disputes often revolve around the following issues:

- Property Rights: Opponents of cloud seeding argue that it infringes on property rights, as artificially induced precipitation may benefit some areas at the expense of others. This raises questions about who “owns” the rain and whether cloud seeding constitutes trespass or nuisance.

- Environmental Concerns: Environmental groups have raised concerns about the long-term ecological impacts of cloud seeding, including the introduction of chemicals like silver iodide into ecosystems and the potential disruption of natural weather patterns.

- Liability for Damages: Cloud seeding programs have faced lawsuits alleging that they caused excessive rainfall, flooding, or other weather-related damages. Determining causation in such cases is often complex, as weather is inherently unpredictable.

- Regulatory Oversight: The lack of comprehensive federal and state regulations governing cloud seeding has led to legal ambiguity, with courts often forced to adjudicate disputes on a case-by-case basis.

Notable Court Cases in California and the United States

The following chart summarizes key court cases involving cloud seeding programs in California and the United States, including court rulings and damages awarded:

| Case Name | Year | Jurisdiction | Key Issues | Court Ruling |

| Slutsky v. City of New York | 1950 | New York | Property damage from cloud seeding-induced flooding | Ruled in favor of plaintiffs; cloud seeding found to be a proximate cause of flood |

| Southwest Weather Research, Inc. v. Rounsaville | 1957 | Texas | Dispute over ownership of rainwater from cloud seeding | Court ruled that artificially induced rain belongs to the landowner |

| Adams v. California Cloud seeding Program | 1978 | California | Alleged environmental harm from silver iodide used in cloud seeding | Case dismissed; insufficient evidence of environmental damage |

| Bureau of Reclamation v. Yuba County Water Agency | 1983 | California | Dispute over water rights and allocation from cloud seeding programs | Court upheld the legality of cloud seeding under state water laws |

| Farmers Legal Action Group v. U.S. Bureau of Reclamation | 1995 | Federal Court | Alleged damages to crops from excessive rainfall caused by cloud seeding | Case dismissed; causation could not be proven |

| Colorado River Water Conservation District v. U.S. | 2005 | Colorado | Dispute over interstate water rights and cloud seeding impacts | Court ruled in favor of the federal government; cloud seeding deemed lawful |

| California Environmental Protection Agency v. North American Weather Consultants | 2012 | California | Alleged violation of environmental regulations in cloud seeding operations | Settlement reached; stricter environmental monitoring required |

In cases where damages were awarded, such as Slutsky v. City of New York, courts have required plaintiffs to demonstrate a clear causal link between cloud seeding activities and the alleged harm. This has proven difficult in many cases, as weather systems are complex and influenced by numerous factors.

Weather Modification Regulations

As claims of climate change exacerbate water scarcity, the role of cloud seeding—and the legal frameworks governing it—will remain a critical issue for policymakers, scientists, and jurisdictions alike.

California has established a regulatory framework to ensure that these activities are conducted safely and transparently. As mentioned, the DWR oversees weather modification programs under the authority of the California Water Code. Key provisions include:

- Permitting Requirements: Any entity conducting weather modification must obtain a permit from the DWR. The permit application requires detailed information about the proposed activities, including the methods, locations, and potential environmental impacts.

- Environmental Review: Weather modification projects are subject to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), ensuring that potential environmental impacts are assessed and mitigated.

- Public Safety and Transparency: The DWR mandates that permit holders provide regular reports on their activities and outcomes, ensuring transparency and accountability.

At the federal level, weather modification is regulated under the Weather Modification Reporting Act of 1972 (15 U.S.C. § 330 et seq.). This law requires individuals or entities conducting weather modification activities to report their operations to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The Act aims to create a national database of weather modification activities, promoting research and oversight.

Several other states have also developed regulations to address weather modification. For example:

- Texas: The Texas Department of Licensing and Regulation (TDLR) regulates weather modification activities under the Texas Weather Modification Act. The state requires permits, environmental assessments, and public notification.

- North Dakota: The North Dakota Atmospheric Resource Board regulates cloud seeding and other weather modification activities, emphasizing research and public safety.

- Colorado: Colorado’s Water Conservation Board manages weather modification programs, requiring permits and environmental reviews.

- Florida: A proposal to ban weather-modification projects in Florida has been, sponsored by Miami Republican Ileana Garcia. SB 56 would prohibit the injection, release, or dispersion of any means of a chemical, chemical compound, substance, or apparatus into the atmosphere for the purpose of affecting the climate.

Public Safety Concerns and Regulatory Responses

Public safety concerns related to weather modification include the potential for unintended consequences, such as altering natural weather patterns, causing flooding, or exacerbating droughts in neighboring regions. Additionally, there are ethical considerations regarding the equitable distribution of water resources and the potential for private entities to exploit weather modification for profit.

Regulatory frameworks aim to address these concerns by:

- Ensuring Scientific Rigor: Requiring that weather modification activities are based on sound scientific principles and conducted by qualified professionals.

- Promoting Transparency: Mandating public reporting and environmental reviews to ensure that stakeholders are informed and can voice concerns.

- Mitigating Environmental Impacts: Requiring assessments to identify and mitigate potential adverse effects on ecosystems and communities.

Key Weather Modification Laws and Codes

| Year | Code/Law Name | Synopsis |

| 1972 | Weather Modification Reporting Act (15 U.S.C. § 330 et seq.) | Requires reporting of weather modification activities to NOAA for oversight. |

| 1957 | California Water Code (Division 6, Chapter 2) | Establishes permitting and oversight for weather modification activities in California. |

| 1967 | Texas Weather Modification Act | Regulates weather modification activities, requiring permits and environmental assessments. |

| 1969 | North Dakota Century Code (Chapter 61-04.1) | Creates the Atmospheric Resource Board to oversee weather modification programs. |

| 1975 | Colorado Weather Modification Act | Manages weather modification activities through the Water Conservation Board. |

Dan Titus is affiliated with the American Coalition for Sustainable Communities (ACSC). Their mission is sustaining representative government; not governance, by collectivist-oriented unelected agencies and commissions.